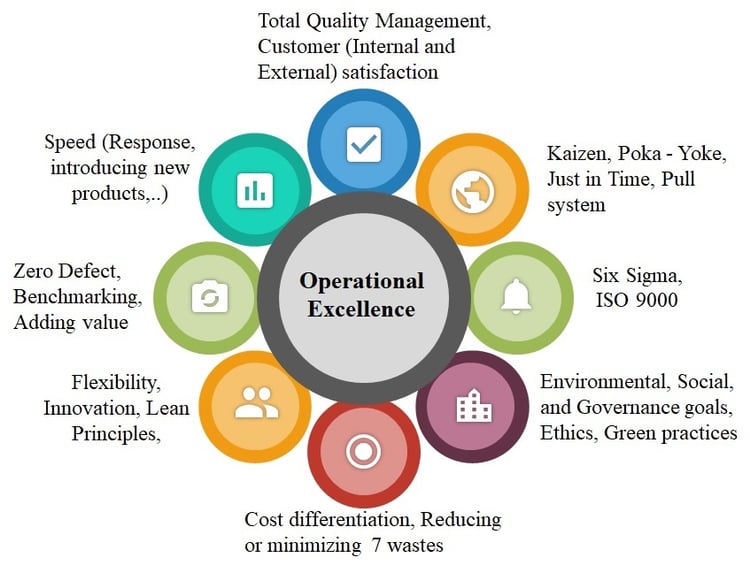

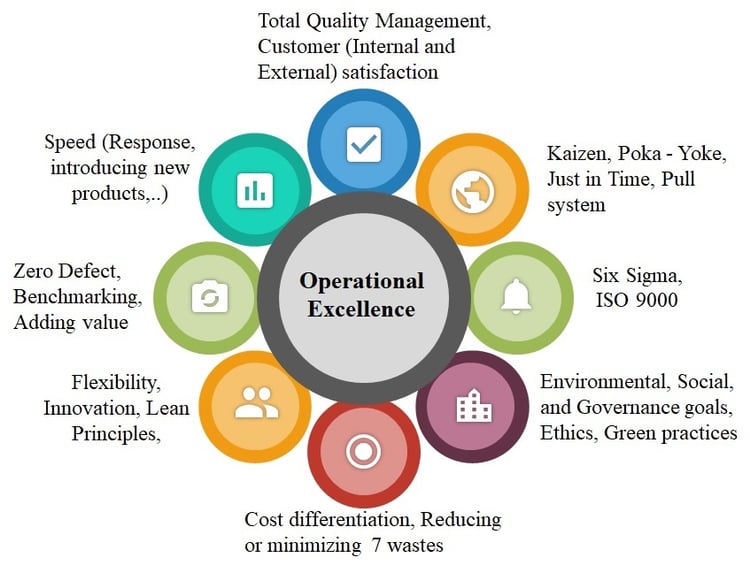

Operational excellence is a broad concept or a laudable objective, not defined precisely or exemplified by demonstration. Although it is regarded as a philosophy by some experts, it is not definable in terms of numbers or expressed as an achievable target in a specified time. Suffice it to say, operational excellence is a state of accomplishment with an overall score considered across multiple parameters.

Operations for a long time focused on production with a specified target per day or any suitable time period with the aim of meeting the demand. Mass production became the order of the day and volume, the only success parameter. But as the operations discipline evolved over a period, several other parameters of assessment started coming into consideration. Top on the list was “quality” and defect-free production. So, the emphasis shifted from product control or end-of-line inspection to process control. Segregation of the output as acceptable or not acceptable based on inspection, and sending the acceptable to the market and the not acceptable to scrap or rework, became the prime concern. However, cost and delivery became equally critical in meeting the customers’ demands. Later, variety became a major variable in bringing competitiveness among the industries. Thus, volume and variety became the basis for categorizing the operations systems under several heads like continuous, mass, batch, and job production systems. These systems differed in terms of facilities, means of production, size, and scale of operations.

Operations parameters evolve

In the next stage, other dimensions were implied upon the production systems as follows:

- Operational Effectiveness - Ability to perform similar activities better than the competitors

- Competitive Superiority – Sustaining a competitive advantage by adopting suitable strategies over the competitors

- Speed – Time is the critical parameter of assessment when observing the organizations’ capabilities. Consequently, speed of response to customers’ queries, demands, and expectations, speed of introducing new products, speed of delivery, and speed of changing according to the requirements.

- Flexibility – in everything associated with an operational system.

- Service – Ability of the production system to offer service to the customers whenever required.

As said by the legendary strategy guru, Michael Porter, cost leadership, differentiation, and focus enable global competitiveness for organizations. This means the operations systems should be able to offer the product or service at a cost suitable to a given market. This demands strict cost control over all aspects of the organization. Differentiation from their competitors should be evidenced by cognizable or noticeable characteristics by the customers.

As the emphasis went up on quality, a global change regarding quality policies and practices started evolving during the eighties and nineties, in the form of ISO standards. These system-wide standards paved the way for establishing generic standards, disregarding the type of industry or product. This further paved the way for international trade and contracts based on the certification of the standards. While the ISO standards do not guarantee the quality of a product, it ensures that the organizations are following the prescribed practices and the procedures are traceable should there be any deviation. Similarly, the other quality movement was led by TQM (Total Quality Management), which was even seen as a panacea to cure all maladies in the industries. TQM later gave its place to the Six Sigma quality system in terms of popularity, and the concept of “zero defect” caught up the attention of the industries. Six Sigma was strongly advocated by companies like Motorola and General Electric, and hence seen as the gold standard in quality. But it is well recognized that “zero defect” is not easy to achieve, given the large number of variables that affect the operations systems.

Influence of Japanese quality and productivity techniques

In almost a similar manner, observing the historical success of policies like “just in time” and “kaizen or continuous improvement” adopted by the Toyota company, the “Toyota Production System” (TPS), became popular across industries the world over. Japanese terms like “jidoka”, “andon”, “hoshin kanri”, among others became common parlance, and the phenomenal success of Japanese companies like Sony, Honda, Toyota, and Canon, to name a few, motivated more industries to follow them, considering it as the route to operational excellence. Again, many companies admitted that it is not easy to adopt TPS as it requires precision, commitment, and uninterrupted supply chains to ensure success. This raised the question, of whether what lead to huge success in Japan may not be so in other places. A similar fate befell “Quality Circles” which were considered the backbone of improving the quality of products or services in organizations, as the research showed that quality circles in many countries did not bring the same result as seen in Japan.

Returning to the question of achieving operational excellence, it is not possible to say whether leading in quality is sufficient to claim excellence. Thus, other parameters have to be brought into the fold of assessing excellence. This shifted the focus of the companies and organizations from the inside of their systems to the external world. The question that assumed significance is what these organizations have been doing or have done to protect the external environment. The operations are observed to be hurting the external environment and the concept of “people, planet, profit” became popularly known as the “triple bottom line” and the impact has been thoroughly investigated.

Focusing externally - beyond the borders of operations systems

Coined by the British consultant, John Elkington in 1994, the triple bottom line started examining a company’s efforts toward a better environment, and sustainability in maintaining safe and environmentally-friendly operations. This concept got a boost with the introduction of “Corporate Social Responsibility”, (CSR).

It is interesting to note that operations that are intended to produce a specific output, unfortunately also create pollution, waste, toxic emissions, unbearable noise, and deplete natural resources. Paper manufacturing, for example, is responsible for the denudation of forests as wood is the prime raw material for producing paper. The waste generated by the industries quite often is not recyclable and thus gets buried or burnt, causing further pollution. Further, the materials used for packing, and other consumables during manufacturing had to be carefully destroyed or scrapped, again demanding additional investment. Thus, a series of “R” techniques namely recycle, repair, refurbish, reduce, and reuse, are strongly advocated to minimize environmental damage.

Concern for environment

The faster depletion of natural materials along with the observed damage to the ecological systems has resulted in the development of environmentally sustainable operations and is now the hot trend all over the world. The environmental, social, and governance, (ESG) goals are being prescribed to the industries, to ensure a safe and sustainable environment. Natural standards look at how an organization shields the climate, including the corporate strategies tending to environmental change. Social standards inspect how it oversees associations with workers, providers, clients, and the networks where it works. Administration manages an organization's initiative, leader pay, reviews, inward controls, and investor freedoms. Currently, ESG initiatives are boosting the operations’ targets and are adopted by many companies. Lean practices focus on waste minimization and speed of flow to enable shorter cycle times and better productivity.

.png?width=600&name=Event%20Email%20Graphic%20Virtual%20Conferences%20(46).png)

Continuing on the ESG goals, the trend is now to “Go Green”. Right from setting up green supply chains to green manufacturing and embedding green practices into all sub-systems of the operations stream are the priorities ahead of the operations people. This should ensure the protection of the environment, conservation of natural resources, and lessening the damage to society in any form.

In conclusion, it can be said that “Operational Excellence” is not a single parameter or a dimension, but is a combination of multidimensional factors illustrated in the previous paragraphs. These factors are in essence the drivers of operational excellence, as depicted in the diagram below.